Gordon Brown's Big UK Gold Sales, 20 Years On

The worst investment decision of modern times...

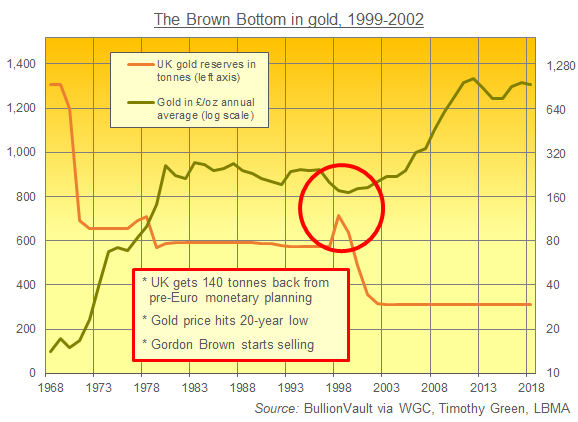

7 May 2019 marks 20 years since the UK's New Labour Government announced a programme which sold 401 tonnes of gold from the nation's then-715 tonne holdings by the end of 2002, writes Adrian Ash at BullionVault.

Ignoring advice from bullion-market insiders and defying resistance from the Bank of England, the move called the very bottom of gold's then-two decade bear market.

- The UK sold some 401 tonnes were sold between 1999 and 2002.

- The average Dollar price achieved was $275.

- That was some $10 per ounce below the price on 6 May 1999, the day before Brown's announcement.

- The average price since Brown's sales ended has been $997 per ounce (an extra 262%).

- Today gold is trading at $1275 (an extra 367%).

Most investors get to make their mistakes in private, hurting only their own savings. But while Gordon Brown's gold sales weren't perhaps his worst policy error – a list topped by the raid on dividend tax credits and the dismantling of City oversight at the Bank of England – the 'Brown Bottom' in gold stands out as the single worst investment decision of modern times.

The Treasury's announcement, slipped out on a quiet Friday afternoon in May 1999, not only coincided with the lowest gold prices in two decades; it actually worsened the drop by 10% before the UK sold any gold that July, because it both shook the bullion market to its foundations and gave it two months' notice of its first auction.

Unnoticed at the time, the Bank of England – then as now central clearing point for the world's wholesale bullion trade – in fact aided the drop in gold prices, because it had lent out up to a quarter of the UK's reserves, earning a small rate of interest from gold-mining firms hedging their future production against the bear market but also boosting the pool of metal available for speculators to borrow and sell short, driving prices still lower with the very gold HMT wanted to sell.

While plainly unwise and now very costly, New Labour's gold sales of 1999-2002 looked perfectly rational at the time. Most of all because everyone else was selling gold too.

What remained of the Gold Standard had been abandoned by the United States nearly three decades earlier. Freed from central-bank control, the gold price then leapt and peaked 10 years later, before slipping and sliding all the way to the millennium.

The Euro had also just launched, unifying Western mainland Europe in a deeply political project with an entirely new currency. And a change of monetary systems always makes the assets backing the old regime look irrelevant. Indeed, if he'd bothered to study history, Gordon Brown could perhaps have looked at Germany's rush to dump silver when it moved to a Gold Standard in the early 1870s, racing to sell down its silver stockpiles and accumulate gold bullion reserves before other countries, most notably France, did the same.

Amid the late 1990s' long boom of solid growth and record-high stock markets, many other Western governments were therefore reducing their legacy gold holdings from the Gold Standard and Bretton Woods eras. So the UK Treasury saw no advantage in being last to sell. Brown himself was also lobbying the International Monetary Fund to sell down its gold holdings, urging the IMF to use that money to write off Third World debt for the millennium.

The ideology driving Brown's central-bank gold sales in fact runs back to Lenin, who wrote in 1921 that the 'complete victory of socialism' would see national gold stocks melted down and recast for public lavatories. Long before then however, many central-bank managers now fear they'll find paper Dollars, Euros and Pounds hanging from a nail on the back of the door. Russia leads national gold buying so far this century, followed by China and India.

New Labour's gold-sales strategy was so ham-fisted that other Western nations immediately came together and made a public agreement that September capping the sector's total sales over the following 5 years. That clarity, plus a promise to lend no more gold, caused a sharp spike and put a floor under gold at that 'Brown Bottom' which the Chancellor had created. Although the CBGA deal has been renewed three times since then, central-bank gold selling has virtually ceased.

The UK's gold sales of 1999-2002 offer three lessons for private investors today:

#1. What feels rational isn't always wise

To many observers at the end of the 20th Century, gold looked like the horse at the end of the 19th – primed to become obsolete thanks to human ingenuity and progress. Western investors were blinded by DotCom IPOs, and pretty much every Western central bank outside the big four (of the US, Germany, Italy and France) were heavy sellers. But outside the developed world, gold's appeal remained untarnished, and the return of Victorian-era financial crises was just around the corner, thanks in good part to the historic hubris of policy-makers. Look beyond your immediate sources of news and information instead of assuming that what's happening now will continue.

#2. How much gold the UK holds means nothing for financial stability or the Pound

Other policies matter much more than how much gold a nation holds in reserve, most of all fiscal deficits and interest rates. In the decade following Brown's decision Sterling rose to 35-year highs on the FX market, peaking back above $2.00. Russia's rapid accumulation of what is now the world's fifth largest official hoard hasn't stopped the Ruble sinking to all-time lows. Venezuela has become a basket-case economy despite holding more than 60% of its foreign reserves in gold.

#3. Sell gold when other markets look darkest, not when it's cheap

Governments face something of a bind in using their gold reserves to counter a crisis, because choosing to sell the ultimate redoubt when things look bad would signal and so worsen the ultimate crisis. Free of such political constraints, private investors can rebalance their assets when gold is high and other investments look cheap.

While past performance is no guarantee of the future, bullion has repeatedly proven a valuable counterweight to other financial assets when they drop. On all 5-year horizons since 1968 for instance, gold has risen 96% of the time that the FTSE All Share has shown a loss. For US investors, gold rose 98% of the time from 5 years before when the S&P index showed a loss.

But hey, like the New York Times asked just 3 days before Gordon Brown announced the UK's 1999 gold sales, who needs gold when you've got central bankers running monetary policy for you?

Email us

Email us