Global Gold Supply vs. the Money Supply

Comparing the global money supply with the world's supply of gold...

JUST HOW DOES the global money supply relate to the global supply of gold? asks Mike Hewitt of DollarDaze.org.

In the essay, we use money supply figures for currency in circulation from 86 selected currencies, from 81 independent countries, and five monetary unions. For the global supply of gold, we use data from the World Gold Council (WGC). Finally, we attempt to interpret the price of gold as a relationship between global money supply and global gold supply.

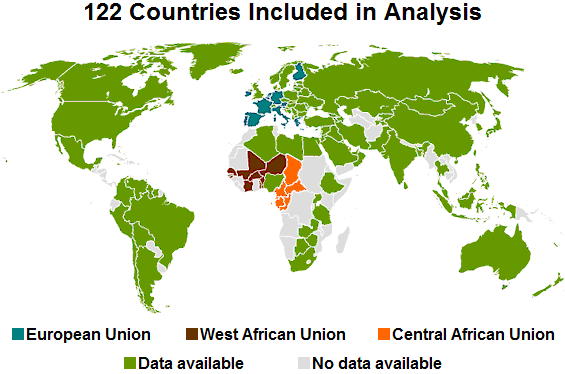

The 81 independent currencies, plus the five currency unions (the European Monetary Union (EMU), commonly known as the Eurozone; the East Caribbean Currency Union, which uses the East Caribbean Dollar; the West African Monetary Union (UEOMA), using the West African Franc; the Central African Monetary Union, technically known as CEMAC, using the Central African Franc; and IEOM, the Institut d'Émission d'Outre-Mer or "Overseas Issuing Institute", which uses the French Pacific Franc) cover a total of 122 countries that make up 98.4% of the world's GDP and 86.1% of the world's population.

The figure below visualizes the coverage of this study. Areas colored grey on the map represent countries without available data. Areas with blue, red, and orange color represent the three most important economic unions, respectively the European, the West African, and the Central African Unions.

Reliable money supply data could not be found for all countries of the world. The five largest economies for which data was unavailable were Morocco, Vietnam, Angola, Sudan, and Cuba. Together these countries comprise 0.6% of world GDP and 2.8% of world population. Their relatively insignificant share of the global economy makes us believe that their exclusion from our analysis would not materially affect our results and our conclusions.

Myanmar (Burma) requires a special note, however, because cross-country money supply comparisons rank Myanmar very high. This apparent paradox arises from the discrepancy between the overvalued official exchange rate and the more realistic "black market" exchange rate.

For the local currency, the 2005 money supply is reported at 1.83 trillion Kyat (MMK). The official exchange rate (6.7147 MMK to US$1) makes this the fifth most valuable currency in the world with a total in circulation of US$273 billion. The unofficial black market exchange rate (1300 MMK to US$1) provides a total value of only $1.4 billion. And in our opinion, the official rate overvalues the currency roughly 200 times and introduces an obvious bias in the data.

Returning to the study, judging quite what qualifies as the "money supply" can prove difficult. The Bank of International Settlements (BIS) provides a link on their website listing central banks for different countries. The following charts use money supply data from these official websites.

But infortunately, there is no unified methodology for calculating different money supply estimates – otherwise known as "monetary aggregates". This presents analytical problems, as different countries use different definitions of money supply. Different definitions, in turn, require different methodologies for calculating different monetary aggregates, which immensely complicates cross-country comparisons. To the best of our knowledge, there is not yet any widely accepted solution to this particular problem.

Money & Gold Supply: The "Ms"

Quite commonly, money is conceptually defined across a continuum from narrow money to broad money. Narrow money typically includes highly liquid forms of money that function as a medium of exchange (i.e. notes and coins), while broad money additionally includes other less liquid forms of money that function as a store of value (i.e. short-term government bonds and bills of exchange).

Monetary aggregates are conventionally denoted in ascending order by M0, M1, M2, M3, and so on. Smaller aggregates like M0 and M1 correspond conceptually to narrow money supply, while larger aggregates like M2 and M3 correspond to broad money supply. We should note that in the heady days of monetarism, economists have further elaborated those aggregates and have devised M4, M5, M6 and even M7.

Most generally and most commonly, but not necessarily uniformly, these definitions apply:

- M0 refers to outstanding currency (banknotes and coins) in circulation, but excludes cash reserves;

- M1 includes M0, demand deposits, and cash reserves at banks;

- M2 includes M1 and savings deposits, conventionally maturing within two years or redeemable at notice within three months;

- M3 includes M2, repurchase agreements, money market funds, and debt securities maturing within two years.

Additionally, not every country publishes all four of the common monetary aggregates.

For example, the US Federal Reserve ceased publishing M3 on May 23, 2006. However, various independent sources have successfully reconstructed the M3 series and have continued to publish it.

For our analysis, we concentrated exclusively on the narrowest measure of money supply, M0. Conceptually, it corresponds best to the monetary interpretation of Gold Bullion – a physical, fungible store of value that has been used as a medium of exchange.

We expect M0 to relate well to the value of gold, although further studies may be necessary to analyze the relationship of gold to higher aggregates, such as M1, M2, and M3.

Money & Gold Supply: Global Currency Comparisons

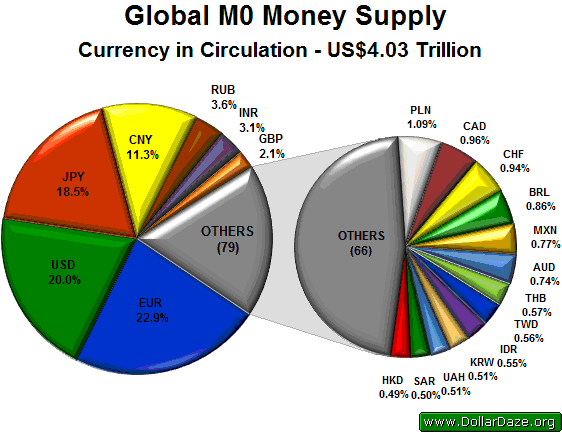

The following pie charts show the relative value of global currencies (M0) when all converted into US Dollars for means of comparison.

All told, the "narrow" global money supply of notes and coins stands near US$4.03 trillion on the M0 aggregate.

The left-hand side of the figure shows that the four largest currencies in circulation comprise nearly three-quarters of the global narrow money supply. Not surprisingly, those currencies are the Euro, the US Dollar, the Japanese Yen, and the Chinese Yuan – corresponding with the world's very largest economic regions.

The right-hand side zooms in on the "other" 79 currencies of the left-hand side that were simply too small to see when shown together with the big currencies. We show the next thirteen most important currencies that comprise more than half of the "other" category.

It is clear from the picture that those thirteen currencies are relatively small compared to the big currencies. Nevertheless, it illustrates well their portion of the global money supply.

Next, we considered narrow money supply growth rates. For the whole dataset, and solely judged from each individual currency's own annual growth rate, the average growth rate of M0 worldwide is 8.2%. It's led by Zimbabwe with its currency now sunk in value to worse than 41 billion per US Dollar thanks to a corresponding explosion in the money supply.

The fastest growing currencies in relative terms all come from smaller economies, such as Azerbaijan, Ukraine and Estonia. But when converted to US Dollars as of 31st Oct. 2008, the fastest growing currencies in absolute terms are shown to the Euro, the Chinese Yuan, the US Dollar and the Russian Ruble.

In absolute terms, in other words, the fastest growing currencies as the major world currencies. The "big" currencies contribute the bulk of increases in the global money supply. And from this particular analysis, we can conclude that a sample of the largest 10-15 currencies in the world can provide a meaningful analysis of the growth rate of global money supply.

Money Supply vs. Gold Supply

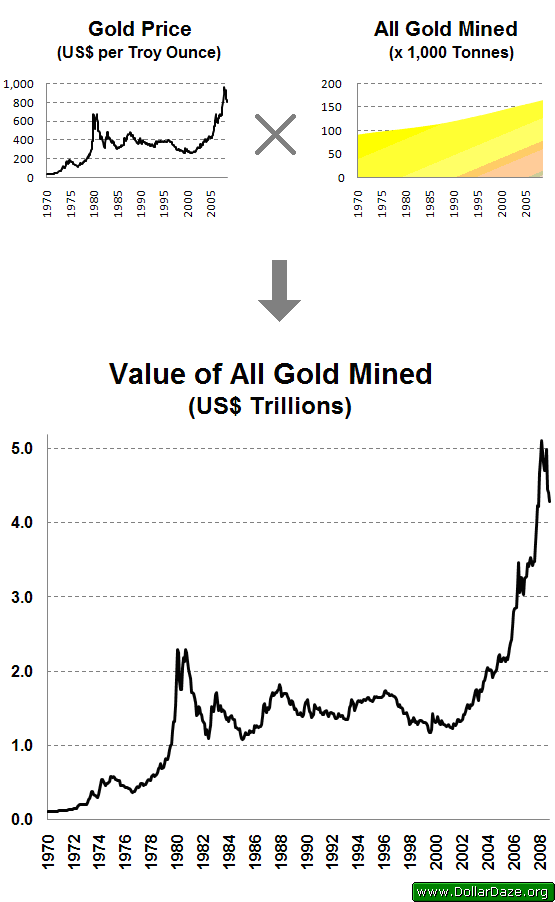

It is estimated by the World Gold Council that a total of 165,547 tonnes of gold have been mined throughout history. This is equivalent to about 5.32 billion ounces.

Most of that gold is currently available as supply at some price (gold is very rarely "lost" for ever), possibly much higher Gold Prices than the current market valuation to bring metal to market. And given that the total gold supply is relatively stable and that very little gold is consumed in industrial processes, the annual increase in the supply of gold from current mining is relatively stable at about 1.5%.

The figure below shows the value of all the gold ever mined. The top left graph shows the Gold Price for the period 1970-2008. The top right graph shows the quantity of all gold mined for the same period. Finally, the bottom graph in the figure shows the product of the price with the quantity.

And all told, by end-October 2008, we calculate the total value of all gold ever mined at US$4.3 trillion. This is just slightly more than the US$4.03 trillion global M0 money supply from our analysis above.

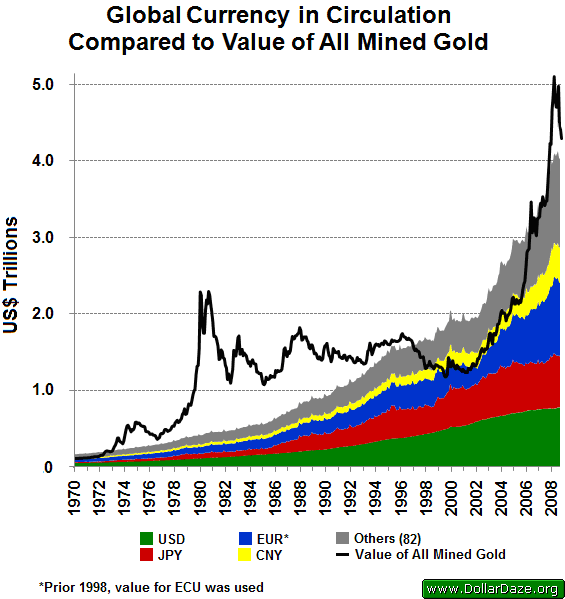

Comparing the Dollar value of global M0 to the Dollar value of all gold then mined, we can chart the two against each other across the last four decades.

The period from 1945 to 1971 is widely known as the "Bretton Woods" era. The chief aim of the Bretton Woods Agreements was to establish the rules for commercial and financial relations among the world's major industrial countries.

The policy required that each country maintained the exchange rate of its currency within a fixed value – plus or minus one per cent – to the US Dollar, which in turn would be convertible to gold at the rate of $35 an oz for foreign governments.

The system collapsed when pressure on the Dollar and thus on US gold reserves led to President Nixon Floating the Dollar Off Gold on August 15, 1971. His move came in response to growing demands from foreign governments to exchange their paper dollars for US Treasury gold.

At that time there was some speculation by professional economists and Wall Street that the price of Gold Bullion would collapse as the US Dollar "would no longer hold it up". In reality, just the opposite occurred. Not only did Gold Prices not collapse, but instead they began a multi-year bull market, reaching an intraday peak of $873 a troy ounce on January 21, 1980.

Our analysis here essentially begins with the collapse of Bretton Woods. The first major observation is that during the 1970s, gold's valuation advanced much farther than money supply. There are two fundamentally different explanations for this phenomenon.

- The first explanation, espoused by neoclassical economists, is that gold is inherently more volatile and more unstable than paper currencies;

- The other explanation, espoused by the School of Austrian Economics, holds the opposite to be true and that price swings in gold reflect the discounted value of expected future inflation.

In other words, Austrian economists contend that the monetary policy associated with paper currencies is inherently unstable, and this instability of paper currencies is magnified when discounted to the current price of gold; this discounting mechanism generates the apparent excessive volatility of gold.

The second fundamental observation is that during the 1970s, gold's valuation rose at significantly faster rates than money supply. Neoclassical economists explain this with the inherently volatile nature of gold. However, volatility simply cannot explain this 10-year trend. Volatility relates to variability in prices around the trend, not to the direction of the trend.

Neoclassical economists have no meaningful explanation here, except to resort to volatility of gold and irrational behavior of gold "bugs". On the other hand, the explanation by Austrian economists is straightforward and logical: As inflation accelerated throughout the 1970s, the discounting mechanism of the Gold Market resulted in accelerating price of gold from the rising inflationary expectations.

The third fundamental observation is the clear possibility of a long-term divergence between the value (or "price") of gold and global money supply. This divergence is obvious for the period of 1980-2000. The neoclassical school has not offered a satisfactory explanation for this phenomenon except to point out disparagingly that gold is a "barbarous relic", "irrelevant" or "dead".

The Austrian explanation, however, is again quite straightforward. The period was generally characterized by disinflation, driven by productivity gains from industry and agriculture, so the discounting mechanism produced lower Gold Prices due to the falling inflationary expectations that more than offset increases in money supply.

This analysis leads us to speculate that while divergences caused by inflationary expectations can last for a very long time, even decades, the long-term price of gold is driven by global money supply.

Email us

Email us