Hey, Loser! How to Win at Investing

Diversification as portfolio protection...

A QUESTION for you, says Tim Price at Price Value Partners.

In the context of your savings and investments, do you want to be a winner, or do you want to avoid being a loser?

An awful lot hangs on your response.

Peter Bernstein's book 'Against the Gods' is not just recommended but compulsory reading for investors who are interested in the broader history of risk.

One of the defining moments of our career was stumbling on the advice offered within it by the 'Renaissance Man' polymath Daniel Bernoulli. Bernoulli offered the following counsel to those involved in managing the wealth of others:

"The practical utility of any gain in portfolio value inversely relates to the size of the portfolio."

In other words, as a general rule, the more people have, the less they need by way of subsequent return. Or to put it another way, in terms that have been validated by the work of Nobel laureates after Bernoulli, wealthy people should be more concerned with capital preservation – in real terms, of course – than with future capital growth.

'Wealthy' is clearly a somewhat subjective term, but we can all relate to the concept of keeping what you have versus putting all of it at risk. This capital preservation approach is all the more important when it relates to those investors who no longer receive regular income by way of paid employment. That is to say, it's especially relevant for retirees and pensioners, who have pots of sacred assets that simply cannot be replaced.

One of the reasons that Bernoulli's advice made such an impact on us was that we came across it during the first dotcom bubble, i.e. the period in the late 1990s through to early 2000 and the Nasdaq bust. At the time, everybody seemed to be amassing huge wealth, quickly, through the ownership of speculative internet stocks. In the words of Lord Overstone,

"No warning on Earth can save people determined to grow suddenly rich."

We suspect that you can pretty much boil the entire stock market down into two fundamental types of participants: those who want to beat the market (or who at least express their performance in market-relative terms) and those, like ourselves, who want to generate a decent absolute return but who don't want to share in the market's inevitable drawdowns at a ratio of 1:1 when they occur.

In other words, our own investment objective is to try and secure as much of the upside potential available through the stock market whilst at the same time trying to protect the downside as far as practicable.

The problem with the aspiration to 'win at all costs' (i.e. to beat the market by a meaningful margin) is two-fold. Firstly, it's extraordinarily difficult (though not impossible – Warren Buffett, Benjamin Graham and the Superinvestors of Graham and Doddsville did actually exist); secondly, you have to accept that in trying to beat the market, by taking more risk than the market, you also run the risk of losing more than the market when things go south.

That's not a risk we're willing to take with our own money, and it's not a risk we're willing to take, at least consciously, with that of our clients.

How bad can underperformance relative to the market be? Consider the drawdown incurred by US equity investors who owned the market in the form of the Dow Jones Industrial Average after the Great Crash of 1929.

In the first instance, the drawdown they suffered between 1929 and 1932 equated to one of 89%. Secondly, US equity investors who owned "the market" at its peak in 1929 weren't made whole again in real terms until 1954. They had to wait 26 years just to get their money back – assuming that they didn't panic and sell out in desperation at the low, which many of them likely did.

If this sounds bad, and it clearly is, now consider how expensive the US stock market is today.

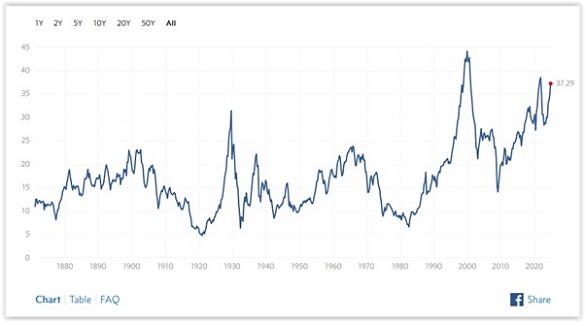

Robert Shiller's cyclically adjusted (i.e. smoothed over the course of a prior decade to take account of the vagaries of the volatility in short-term corporate earnings) price / earnings ratio for the S&P 500 index – more representative of the entire US economy than that of the 30-stock Dow – now stands at roughly 37 times, or more expensive than it was in 1929 and only lower than its prevailing level during the first dotcom bubble.

Its long run average for the past 150 years is roughly 17 times. We are at more than twice that level today.

The late 1990s showed us that the Shiller p/e can remain unnaturally elevated for a while. And we're not in denial about the 'new economy' and the capital-light model that can be exploited in some cases to achieve global scale quickly by digital businesses (though it turns out AI is fantastically and expensively energy-intensive).

Our point is somewhat subtler: We don't think that human nature quickly changes. And we believe in reversion to the mean.

Interest rates have started to rise over the past couple of years after three-and-a-half decades of trending down towards zero. Most fund managers have never experienced a higher interest rate cycle.

So we make no apology for focusing on a 'safety first' approach towards managing your investments. Our focus is and will always be on capital preservation as much as on future capital growth, and we define capital preservation as primarily a focus on defensive value with some form of margin of safety.

You can try and be a winner, and put a significant part of your savings pot at risk. Or you can try not to be a loser, and focus on an absolute return (cash-plus or inflation-plus) objective instead.

Our thesis is that over the long run, by avoiding the big drawdowns consistent with market-relative investing, we may well end up beating the market anyway – by preserving more capital during the downturns than index-relative investors do. It then becomes a matter of compounding at an overall higher rate, because we manage to avoid some of the wrenching and inevitable losses that occur during bear markets, and from which it can be sometimes very difficult ever to recover. The post-1929 experience being a case in point.

There are some specific aspects to our 'not losing' thesis. One is that a properly diversified investment portfolio in 2024 should include 'value' equities (shares in cheap but high quality listed businesses); systematic trend-following funds (uncorrelated to stock and bond markets); and real assets, notably the monetary metals, gold and silver, and related investments trading, again, cheaply versus their historic range.

Why 'value' equities?

Because common stocks have, over the last two centuries, been one of the best-performing assets to own, at least in the context of the US and UK markets. Other regions haven't been so lucky. The refinement is then to concentrate primarily on 'value' stocks – i.e. shares of high quality businesses run by principled, shareholder-friendly management with a track record of generating strong shareholder returns, but only when those shares can be bought at a meaningful discount to their inherent value.

Why systematic trend-following funds? The investment world has got more risky, not less, since the Global Financial Crisis. Global politics are a mess, and a rising interest rate cycle will play merry hell with traditional portfolios, and not least with bonds. Managers pursuing an unconstrained (long and short) diversified trading thesis will be more appropriate than plodding index-trackers. The time to use index-trackers will be after the next major correction, when markets are once again objectively cheap.

Why 'real assets' and the monetary metals? Because we believe in sound money. Gold and silver have always been "money good" – nobody has ever been forced to use them as money; their use arose spontaneously in free markets and economies over thousands of years. Governments today have to use the rule of law and coercion to get us to pay our taxes (and pretty much everything else) in fiat currency. Given the extent to which the debt markets have continued to expand since 2008, we suspect that the next phase in this rolling financial predicament will be highly inflationary, as governments continue to prime the monetary pump to avoid a gigantic reset (which may come anyway). Gold and silver, of course, cannot be printed.

As Mohamed El-Erian points out in 'The Financial Times' ('Why the west should be paying more attention to the gold price', 21 October 2024):

"Gold's 'all-weather' characteristic signals something that goes beyond economics, politics and higher-frequency geopolitical developments. It captures an increasingly persistent behavioural trend among China and "middle power" countries, as well as others.

"Over the past 12 months, the price of an ounce of gold on international markets has increased from $1947 to $2715, a gain of almost 40 per cent. Interestingly, this march up in price has been relatively linear, with any pullback attracting more buyers. It has occurred despite some wild swings in expected policy rates, a wide fluctuation band for benchmark US yields, falling inflation and currency volatility.

"What is at stake here is not just the erosion of the Dollar's dominant role but also a gradual change in the operation of the global system. No other currency or payment system is able and willing to displace the Dollar at the core of the system and there is a practical limit to reserve diversification. But an increasing number of little pipes are being built to go around this core; and a growing number of countries are interested and increasingly involved.

"What has been happening to the gold price is not just unusual in terms of traditional economic and financial influences. It also goes beyond strict geopolitical influences to capture a broader phenomenon which is building secular momentum.

"As it develops deeper roots, this risks materially fragmenting the global system and eroding the international influence of the Dollar and the US financial system. That would have an impact on the US's ability to inform and influence outcomes, and undermine its national security. It is a phenomenon that western governments should pay more attention to."

There is one crucial caveat to this diversified and 'value' approach, however. It requires patience – especially with regard to the 'value' equity component.

Would you have sold?

That caveat about requiring patience, though, bears repeating. Perhaps the best way of expressing it is via the 1970s performance of Berkshire Hathaway stock – one of the best performing US equity investments of the last 50 years – versus the market.

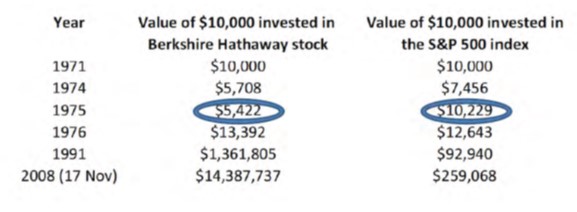

The data below shows you how you would have fared if you'd put $10,000 into shares of Berkshire Hathaway and $10,000 into the S&P 500 stock index in 1971. It tells something of a story.

The figures should speak for themselves. Warren Buffett is a multi-billionaire because of this long-term outperformance of the market.

But in 1971, you didn't know what the future would hold. What you did experience, by holding Berkshire Hathaway until 1975, was losing half of your money, even while the rest of the market recovered, and 4 years of dismal returns.

Simple question. In the light of just those four years of data alone, what do you honestly think you would have done? Would you have sold?

Which is why it's crucial to take the long view. Markets are not entirely efficient, nor are they entirely rational.

What matters to us, as shareholders in any company, is how the company is performing at an operational level. Is it still making decent profits? Is it still using its cash wisely?

For as long as the company is operating decently or better, we try not to care too much about the stock price. The company can control its profits (more or less) but it can do next to nothing about controlling its stock price. That is almost entirely in the hands of the mob.

No matter how much money you have and no matter how smart you are, there are only so many things you can do to protect your financial future. There is always something that can catch you unawares.

There is also a pervasive sense among the electorates of the West that they have somehow been cheated by the forces of 'crony capitalism' – and we share that resentment. As Jeffrey Tucker writes for the Brownstone Institute:

"The global Covid response was the turning point in public trust, economic vitality, citizen health, free speech, literacy, religious and travel freedom, elite credibility, demographic longevity, and so much more. Now five years following the initial spread of the virus that provoked the largest-scale despotisms of our lives, something else seems to be biting the dust: the postwar neo-liberal consensus itself."

Peter St Onge, for the same platform, writes:

"Authoritarianism is back across the West – from Europe to the Biden-Harris censorship regime that would fit perfectly in Communist China.

"I think many of us were surprised during Covid to realize just what the supposedly liberal West has become: Essentially the Soviet Union but with better uniforms."

The politics of our time have now become hopelessly polarised and admit, seemingly, to no compromise on anything. That leaves the very real threat of an ultimately undelivered Brexit and – almost infinitely worse still – the threat of unreconstructed Marxist governments across the supposedly developed world.

So the real impact of the Global Financial Crisis has only just started to be felt at a social level. This is in part what happens when governments fail to address major problems in a serious way, the first time around.

In a justly famous essay, Charles 'Charley' Ellis, the investment consultant who founded Greenwich Associates, pointed out, citing the work of scientist Simon Ramo in the process, that there was not in fact one game of tennis, but two. There was tennis as played by the professionals, and then tennis as played by the rest of us.

In the professional game, the player wins points. In the amateur game, the player loses points.

Professional tennis players are a dream to watch, as they vault, dive, lunge and volley. They rarely make errors.

Amateur tennis players: not so much.

The tennis pro is playing a winner's game. Victory is down to winning more points than your opponent. The amateur is playing a loser's game. Victory is achieved, and not very stylishly, by getting a higher score than your opponent, because he or she loses more points than you do. Amateur tennis is a game full of errors.

Ramo even tallied the scores. The verdict: in professional tennis, about 80 percent of the points are won. In amateur tennis, roughly 80 percent of the points are lost, i.e. in unforced errors.

For the amateur tennis player, the best strategy for victory is to avoid mistakes. The best way to avoid mistakes is to be conservative and keep the ball in play. Give the other player enough rope to hang himself.

Clearly the analogy is useful for the private investor versus the alleged professional.

Although human nature doesn't change, the composition of the financial markets has evidently changed over the past century. Ellis suggests that during the 1930s and 1940s – a period during which the work of the value investor Benjamin Graham would come to growing prominence – preservation of capital and prudent investment approaches would come to dominate. The bull market of the 1950s attracted new types of aggressive, hot money investors. The people who were drawn to the Wall Street of the 1960s had always been winners – in debating teams or in sports teams. But as the markets sucked in more and more winners and people who urgently wanted to win, the dynamic of the markets changed.

In the 10 years prior to Ellis' 1975 essay, institutional investors went from representing 30 percent of the turnover on Wall Street to 70 percent.

Ellis' advice to anyone trying to beat the professionals at their own game?

- Know your investment policies very well and play according to them consistently. Let the other fellow make the mistakes. Let him track the benchmarks – leave your own portfolio entirely unconstrained.

- Keep it simple. In the words of the golfer Tommy Armour, "Play the shot you've got the greatest chance of playing well." Wait for the fat pitch. Do nothing otherwise. This is a luxury the institutional fund manager does not have.

- Focus on defence. In a loser's game, researchers should spend most of their time making sell decisions, not purchases. To put it another way, limit your number of purchases. Better a concentrated portfolio where each of the positions is well understood, than a 'diworsified' portfolio consisting of little or no underlying investment conviction. Data strongly suggest that the optimal number of portfolio holdings is around 16 or so. (Within our fund and within our discretionary portfolios, we target between roughly 15 and 30 holdings.) Many successful investors get by with less than 10. You don't need to own "the market". A focused portfolio of high conviction stocks is something you can hold that most professional investors simply can't.

- Don't take it personally. "Most of the people in the investment business are "winners" who have won all their lives by being bright, articulate, disciplined and willing to work hard. They are so accustomed to succeeding by trying harder and are so used to believing that failure to succeed is the failure's own fault that they may take it personally when they see that the average professionally managed fund cannot keep pace with the market.." You don't have to worry about peer group performance. There's no rush – you just need to shepherd your capital so that you can stay in the game.

Value investing gives you an automatic edge over most market professionals because it's a game very few of them can even play. They don't have the luxury of time, and they don't have the flexibility to go off benchmark and invest freely into the best opportunities. They are more concerned with keeping their jobs and running with the herd than with maximising returns.

In summary, ask yourself two questions: what does it cost? And how much is it worth? Then quietly ask yourself a third: do I sincerely want to be rich? And finally ask yourself a fourth: do I sincerely want to stay rich?

Email us

Email us