Back to 1909 with Trump's Tariffs

Global trade war explodes...

OUCH, says Frank Holmes at US Global Investors.

Global markets are in freefall in response to President Donald Trump's universal 10% tariff on all goods being imported into the US, with as many as 60 countries facing "reciprocal" tariffs on top of that.

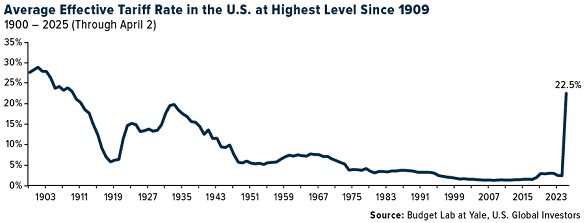

When we combine all new tariffs in 2025 so far, including the raft of reciprocal tariffs announced last Wednesday, we're looking at an average effective rate of 22.5%, according to Yale's Budget Lab.

That's the highest such rate since 1909 − the same year that President Howard Taft proposed the idea of an income tax to Congress.

As I have pointed out before, tariffs are a type of tax paid for by domestic import-export companies, who often pass the additional cost on to consumers. This can turbocharge domestic inflation.

Tariffs can also lead to full-blown trade wars, as we saw in the federal government's previous attempts to raise revenue through the taxation of imported goods.

The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, enacted in 1930, is widely believed to have exacerbated the effects of the Great Depression, as global trade tanked a whopping 65%. A few decades prior, then-Representative William McKinley's tariff act triggered retaliation from other nations, leading to higher prices for US consumers.

(If you need to brush up on your Smoot-Hawley history, I recommend the famous "Anyone? Anyone?" scene in 1986's Ferris Bueller's Day Off.)

As was the case then, we're already seeing retaliatory tariffs. China announced that it will impose a 34% duty on all goods imported from the US. If this weren't enough, automobile imports face a steep 25% tariff. Trump claims he "couldn't care less" if foreign manufacturers raise prices for US consumers, and from the looks of it, they may need to − and significantly so, in some cases.

Mitsubishi, for instance, will need to increase the price of its vehicles by more than 20% here in the US to offset the new levy, according to estimates by CLSA.

The manufacturer expected to fare the best under this tariff regime is Tesla, whose supply chain is well-integrated in the US. More than 62% of the company's facilities are located domestically, with approximately a quarter of its suppliers also based in the US, according to Bloomberg data. By comparison, fewer than half of Ford's facilities worldwide are currently located in the US.

This could be constructive for Tesla, whose stock has lost over half of its value since its peak in mid-December, making it one of the worst performers of the year so far. The carmaker's quarterly sales fell a significant 13% in the first quarter compared to the same period last year, due mainly to political backlash against CEO Elon Musk.

When it comes to new home purchases, bad economic news could be good news. Mortgage rates generally track the yield on the 10-year Treasury, which dropped below 4% on Friday due to concerns about the trade war. Bond yields generally fall when prices rise.

Granted, home prices in the US are still hovering near record highs, but current homeowners may be able to refinance sooner than expected.

Lower yields are also good for gold. Because it's a non-interest-bearing asset, gold starts to look more attractive as yields fall, especially when inflation remains historically elevated, as it is now. The 10-year yield is nominally 4.1% right now, but when you factor in the 2.8% headline inflation rate from February, the real yield is closer to 1.3%.

If yields fall further or if inflation jumps higher due to tariffs, we may end up with negative real yields, which have historically been bullish for gold prices.

The yellow metal is trading down as it's swept up in the broader selloff, and I believe investors should strongly consider buying these dips. Gold just notched its best quarter since 1986, ending March at $3123 per Troy ounce, and there could be further upside momentum.

Email us

Email us