The Debt Riddle Making Investors Worse Off

Policies aimed at solving debt crises are bad news for investors...

THERE WAS a time when it was more-or-less taken for granted that you could save money, put it aside, and earn enough interest to be better off than when you started, writes Ben Traynor at BullionVault.

As the world continues to struggle with the aftermath of an enormous credit boom and its subsequent bust, though, this kind of objective seems hopelessly naïve.

Events in Europe and the US this week are the latest reminder of this. To see why, let's start with a riddle:

If I owe you €10,000, and the amount of money I have is zero, is it possible to let me off the hook without you taking a loss?

The question is rather silly, yet it is analogous to the one facing policymakers in Europe right now as they decide what to do about Greece.

Here's the problem in a nutshell: Greece was tasked with reducing its debt-to-GDP ratio to a 'sustainable' 120% by 2020 (by complete coincidence the ratio for the Eurozone's biggest debtor Italy at the time the target was set last year). That wasn't not enough time, Euro politicians decided last week, so they extended the deadline to 2022.

Christine Lagarde, managing director at the International Monetary Fund, was not happy about this. She would rather see the deadline stay as 2020, with the debt being reduced directly by further write downs. Germany and other Euro members are averse to this since it would impose further losses on creditors. Private sector Greek bondholders were burned back in February, compelled to take losses as part of a restructuring deal.

A further write down might also hit the European Central Bank, which has already agreed to forego profits on its Greek bonds. If the ECB takes actual losses, would this not amount to central bank financing of government debt – something prohibited by European treaty? According to Germany, it would.

So we have a problem where a debtor cannot pay and creditors don't want to take a hit (and in the case of the ECB may not legally do so, many argue). Naturally the first maneuver is to give the debtor a bit more time, which is exactly what Eurozone politicians did last week. This will only achieve so much though. The latest figures show the Greek economy is still contracting; policymakers will have to buy an awful lot of time if Greece is to pay down the debt through economic growth alone.

So what else can be done? This is where the people at the top are yet to reach agreement. One of the suggestions doing the rounds is to lower the interest rate Greece pays on its bailout loans, a classic move to lower the real, inflation-adjusted value of debt.

Just ask Ben Bernanke. In a speech given this week the Federal Reserve chairman reiterated the need to maintain loose monetary policy for the foreseeable future.

"A highly accommodative stance of monetary policy will remain appropriate for a considerable time after the economic recovery strengthens," he said.

Bernanke also repeated his call for US lawmakers to sort out the deficit, arguing that monetary policy can only provide a supportive environment; it cannot solve fiscal problems. Not the Bernanke is a deficit hawk:

"Even as fiscal policymakers address the urgent issue of longer-run fiscal sustainability," Bernanke said, "they should not ignore a second key objective: to avoid unnecessarily adding to the headwinds that are already holding back the economic recovery."

In other words, the US government should maintain borrowing near record levels, while also trying to get borrowing onto that sustainable path.

It's a tricky balance, but Bernanke seems confident America's politicians can pull it off:

"Fortunately, the two objectives are fully compatible and mutually reinforcing. Preventing a sudden and severe contraction in fiscal policy early next year will support the transition of the economy back to full employment; a stronger economy will in turn reduce the deficit and contribute to achieving long-term fiscal sustainability. At the same time, a credible plan to put the federal budget on a path that will be sustainable in the long run could help keep longer-term interest rates low and boost household and business confidence, thereby supporting economic growth today."

He may be proven right. But whether he is or not, that "accommodative" policy of below-inflation interest rates is here to stay.

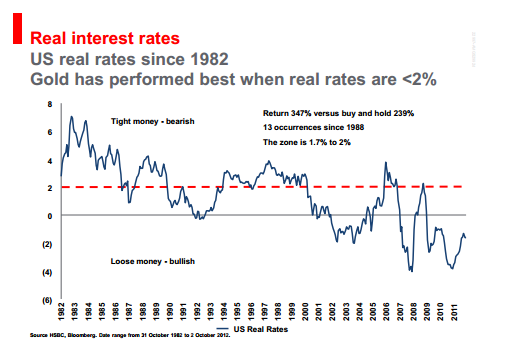

That should give continued support to the Gold Price. The chart below is from a presentation by Charlie Morris, head of global asset management at HSBC, given at last week's London Bullion Market Association annual conference.

Morris points out that when the annual real rate of interest (i.e. how much you make adjusted for inflation) has been below 2%, gold has tended to do well:

Many investors today would be happy with a real return of flat zero – at least they wouldn't be losing ground.

As the world grapples with the plight of sovereign debtors, though, the idea of getting a reliable real return from an investment is sadly starting to seem rather out-of-date. Moody's downgraded France this week; here's one of the reasons it gave in its ratings rationale:

"...unlike other non-euro area sovereigns that carry similarly high ratings, France does not have access to a national central bank for the financing of its debt in the event of a market disruption."

In other words, if France could just print what it owes, it could probably still be rated triple-A. Creditors would get back the money they lent out, and there would only be the small matter of it being worth a lot less than when they lent it.

That is today's reality. It may be unavoidable given the sheer size of the debt problems affecting much of the globe; but it's a pretty raw deal for those trying to grow or even hang onto the value of their savings.

Thinking about a Gold Investment? Make it safer, cheaper and easier with BullionVault...

Email us

Email us