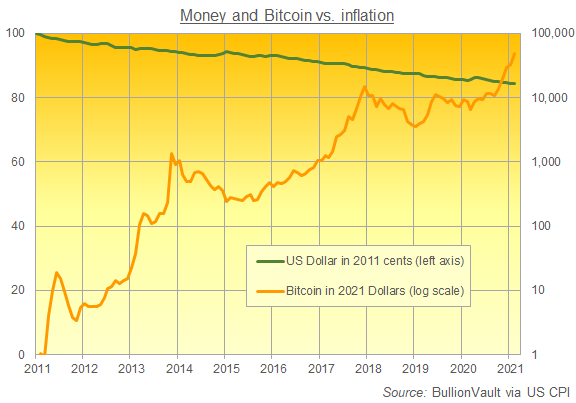

Money and Bitcoin Compared

- that it's becoming progressively easier to get hold of money,

- that the value of their collateralised asset is rising high above the loan it supports, and

- that each time the bank wants to renegotiate the loan, the interest rate rises, and the length of the available term for a given rate reduces.

Email us

Email us